Mexico: after a year in power, Andrés Manuel López Obrador is failing to contain violence

When Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, was sworn into office in December 2018 he promised swift action to stem the bloody crime wave that has ravaged the country in recent years.

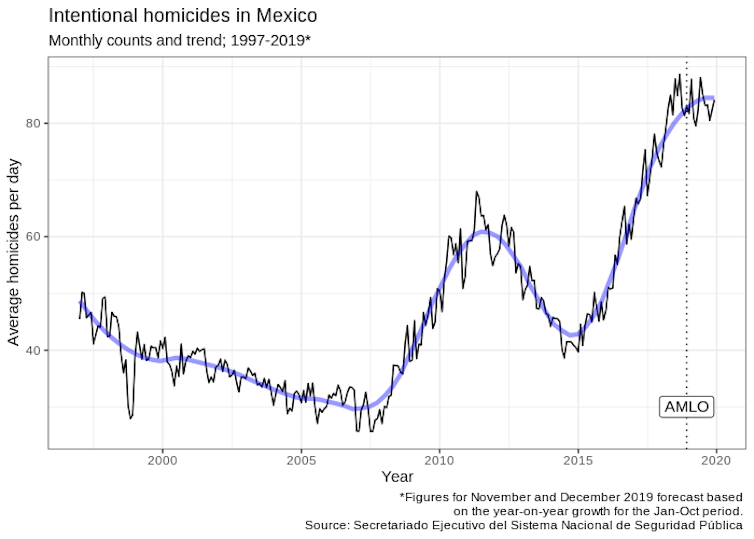

Faced with record-shattering homicide counts in 2017 and 2018, the new government promised drastic reductions in crime. López Obrador, known as AMLO, launched an ambitious security plan focused on tackling the “root causes” of crime, ending the war against organised crime and overhauling security institutions, such as the federal police.

However, the number of homicides remain at an all time high and the mishandling of repeated crises suggest that López Obrador’s government is overwhelmed by the deteriorating security situation in the country.

Since taking office, the president has repeatedly claimed that homicides started to drop since he came to power. But the government’s own data contradicted this. A closer inspection shows that the homicide rate has not decreased over the past year, although it has stopped its vertiginous increase for the first time in almost five years.

However, the news is hardly a cause for celebration. The current rate – which hovers between 80 and 100 homicides per day – is the highest the country has experienced since current records began in 1997. Sadly, the current lull is no guarantee that homicides will decrease in the future, and they may well increase again – as happened during the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto between 2012 and 2018.

Hugs, not bullets

Vowing to end the “war against organised crime”, the president opted for a non-confrontational approach to security, aiming to dissuade offenders and organised criminals through social policy, rather than through policing and criminal justice – a strategy the president summarises as “hugs, not bullets”. In early September, he urged criminals to behave and think of their mothers.

The government has sought to scale back the lethality of its security forces, but several crises suggest that its light-touch approach is not working.

For example, 13 state police officers were executed in October by 30 cartel gunmen in an ambush in Aguililla, Michoacán, a state in western Mexico. In response, the president offered no short-term strategy and instead blamed “social decomposition” in the region, vowing to continue pushing his economic and social policy – which has been criticised for being arbitrary and ill-defined.

The same month, a more damming crisis erupted following the botched capture and subsequent release of Ovidio Guzmán, son of notorious drug trafficker, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, as cartel gunmen laid siege to Culiacán, capital of Sinaloa state, demanding the release of their leader. The president defended yielding to the cartel’s demands, arguing that not doing so would have led to a bloodbath. But critics widely panned López Obrador for his government’s mishandling of the Culiacán crisis, noting that it would only embolden other criminal groups.

Three women and six children of a Mormon family were then massacred in northern Mexico by a criminal group in November. As the victims held Mexican and American citizenship, the episode prompted the US president, Donald Trump, to consider designating Mexican criminal groups as foreign terrorist organisations, heightening tensions between the two countries. Trump ultimately decided against it.

Read more: Mormons in Mexico: A brief history of polygamy, cartel violence and faith

A lack of understanding

At the root of the government’s failing security policies lie fundamental misunderstandings of Mexico’s criminal phenomenon. Specifically, López Obrador believes that violence is mainly caused by government security policy and economic strife.

There is evidence that certain security strategies can escalate cycles of violence. But organised crime violence is a deeply complex phenomenon caused by a wide range of factors – such as international drug trends, competition between and within cartels, and the embeddedness of organised crime groups in local communities.

The way in which the authorities intervene is certainly important, but it is not the only factor causing increases in violence. Furthermore, the absence of violence would not necessarily mean that organised crime groups are defeated, as it could signal a condition known as “pax mafiosa”, in which criminal groups rule a territory in relative peace.

Assuming that criminal behaviour is caused by economic strife is a common, though too simplistic view of the problem. Research suggests that criminal behaviour is far more complicated than that, noting that it emerges in certain places and times and not in others due to a complex interaction of personal and contextual attributes. Of course, this does not mean that social policies should be abandoned, as they are important to improving welfare in general. But it’s unlikely that they will be enough to turn the tide of criminal violence currently rocking Mexico.

If the government is to successfully tackle violence related to organised crime in Mexico, it must first take steps to acknowledge the inherent complexity of the problem. Rather than proposing a one-size-fits-all approach, specific policies need to be devised based on a nuanced understanding of the diverse criminal phenomena affecting specific places and their reality.![]()